Answer to Question 1

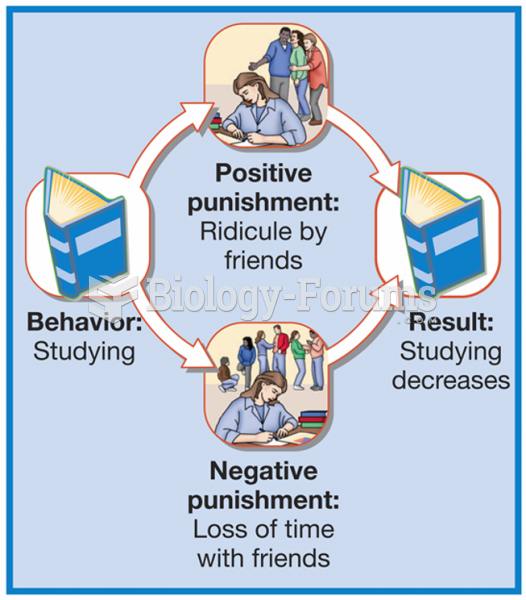

Answer: Frequent punishment promotes immediate compliance but not lasting changes in behavior. The more harsh threats, angry physical control, and physical punishment children experience, the more likely they are to develop serious, lasting mental health problems. These include weak internalization of moral rules; depression, aggression, antisocial behavior, and poor academic performance in childhood and adolescence; and depression, alcohol abuse, criminality, physical health problems, and family violence in adulthood.

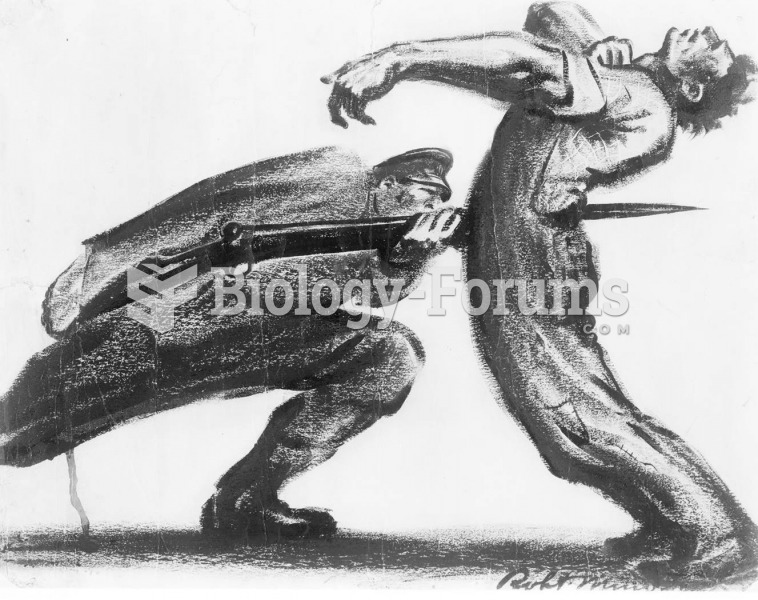

Parents often spank in response to childrens aggression, yet physical punishment itself models aggression. Harshly treated children develop a chronic sense of being personally threatened, which prompts a focus on their own distress rather than a sympathetic orientation to others needs. Children who are frequently punished learn to avoid the punitive parent, who, as a result, has little opportunity to teach desirable behaviors.

By stopping childrens misbehavior temporarily, harsh punishment gives adults immediate relief. For this reason, a punitive adult is likely to punish with greater frequency over time, a course of action that can spiral into serious abuse. Children, adolescents, and adults whose parents used corporal punishmentphysical force that inflicts pain but not injuryare more accepting of such discipline. In this way, use of physical punishment may transfer to the next generation.

Answer to Question 2

Answer: Children first acquire skills for interacting with peers within the family. Parents influence childrens peer sociability both directly, through attempts to influence childrens peer relations, and indirectly, through their child-rearing practices and play. Preschoolers whose parents frequently arrange informal peer play activities tend to have larger peer networks and to be more socially skilled. In providing play opportunities, parents show children how to initiate peer contacts. And parents skillful suggestions for managing conflict, discouraging teasing, and entering a play group are associated with preschoolers social competence and peer acceptance. Many parenting behaviors not directly aimed at promoting peer sociability nevertheless influence it. For example, secure attachments to parents are linked to more responsive, harmonious peer interaction, larger peer networks, and warmer, more supportive friendships during the preschool and school years. The sensitive, emotionally expressive communication that contributes to attachment security is likely responsible. Warm, collaborative parentchild play seems particularly effective for promoting peer interaction skills. During play, parents interact with their child on a level playing field, much as peers do. And perhaps because parents play more with children of their own sex, mothers play is more strongly linked to daughters competence, fathers play to sons competence.