Answer to Question 1

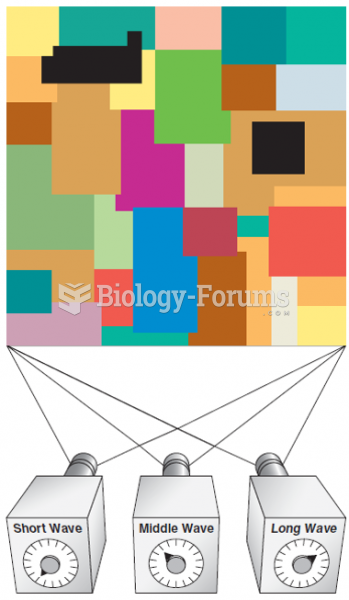

An area that illustrates much of the research on linguistic universals focuses on color names. These words provide an especially convenient way of testing for universals. Why? Because people in every culture can be expected to be exposed, at least potentially, to pretty much the same range of colors. In actuality, different languages name colors quite differently. But the languages do not divide the color spectrum arbitrarily. A systematic pattern seems universally to govern color naming across languages. Consider the results of investigations of color terms across a large number of languages. Two apparent linguistic universals about color naming have emerged across languages. First, all the languages surveyed took their basic color terms from a set of just 11 color names. These are black, white, red, yellow, green, blue, brown, purple, pink, orange, and gray. Languages ranged from using all 11 color names, as in English, to using just two of the names, as in the Dani tribe of Western New Guinea. Second, when only some of the color names are used, the naming of colors falls into a hierarchy of five levels. The levels are (1) black, white; (2) red; (3) yellow, green, blue; (4) brown; and (5) purple, pink, orange, and gray. Thus, if a language names only two colors, they will be black and white. If it names three colors, they will be black, white, and red. A fourth color will be taken from the set of yellow, green, and blue. The fifth and sixth will be taken from this set as well. Selection will continue until all 11 colors have been labeled. The order of selection within the categories may, however, vary between cultures.

Answer to Question 2

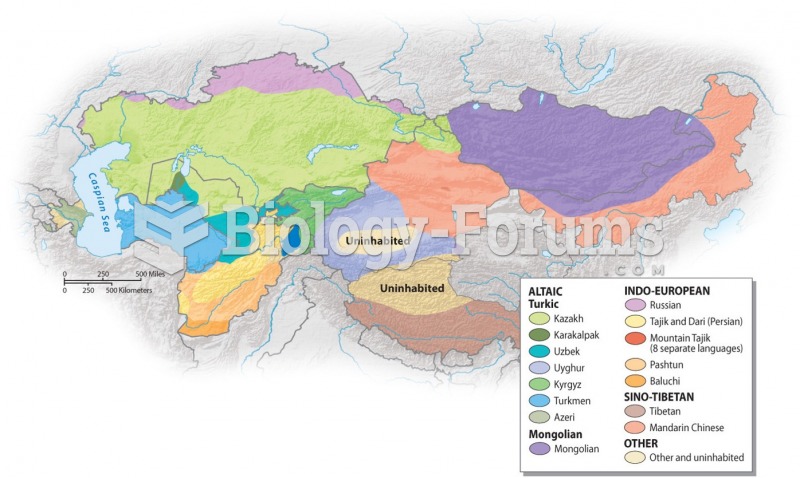

Sometimes when people of two different language groups are in prolonged contact with one another, the language users of the two groups begin to share some vocabulary that is superimposed onto each group's language use. This superimposition results in what is known as a pidgin. It is a language that has no native speakers. Over time, this admixture can develop into a distinct linguistic form. It has its own grammar and hence becomes a creole. An example of a creole is the Haitian Creole language, spoken in Haiti. The Haitian Creole language is a combination of French and a number of West African languages. Modern creoles may resemble an evolutionarily early form of language, termed protolanguage.