Answer to Question 1

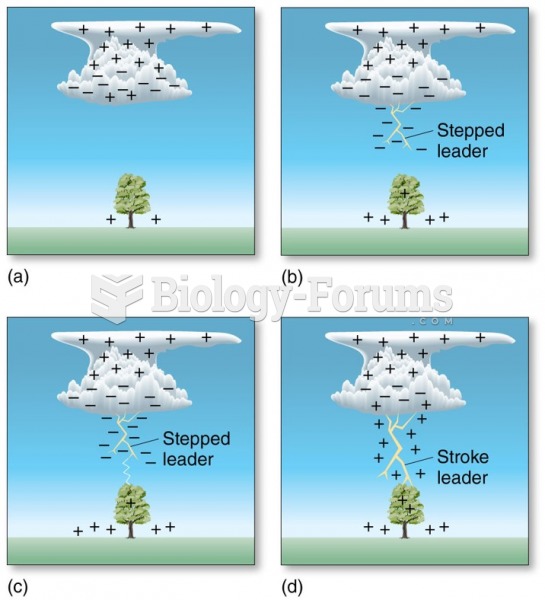

ANSWER: One technique that has shown some success in suppressing lightning involves seeding a cumulonimbus cloud with hair-thin pieces of aluminum about 10 centimeters long. The idea is that these pieces of metal will produce many tiny sparks, or corona discharges, and prevent the electrical potential in the cloud from building to a point where lightning occurs. While the results of this experiment are inconclusive, many forestry specialists point out that nature itself may use a similar mechanism to prevent excessive lightning damage. The long, pointed needles of pine trees may act as tiny lightning rods, diffusing the concentration of electric charges and preventing massive lightning strokes.

Answer to Question 2

ANSWER: Light travels so fast that you see light instantly after a lightning flash. But the sound of thunder, traveling at only about 330 m/sec (1100 ft/sec), takes much longer to reach your ear. If you start counting seconds from the moment you see the lightning until you hear the thunder, you can determine how far away the stroke is. Because it takes sound about 5 seconds to travel one mile, if you see lightning and hear the thunder 15 seconds later, the lightning stroke (and the thunderstorm) is about 3 miles away. When the lightning stroke is very closeon the order of 100 m (330 ft) or lessthunder sounds like a clap or a crack followed immediately by a loud bang. When it is farther away, it often rumbles. The rumbling can be due to the sound emanating from different areas of the stroke. Moreover, the rumbling is accentuated when the sound wave reaches an observer after having bounced off obstructions, such as hills and buildings.