Answer to Question 1

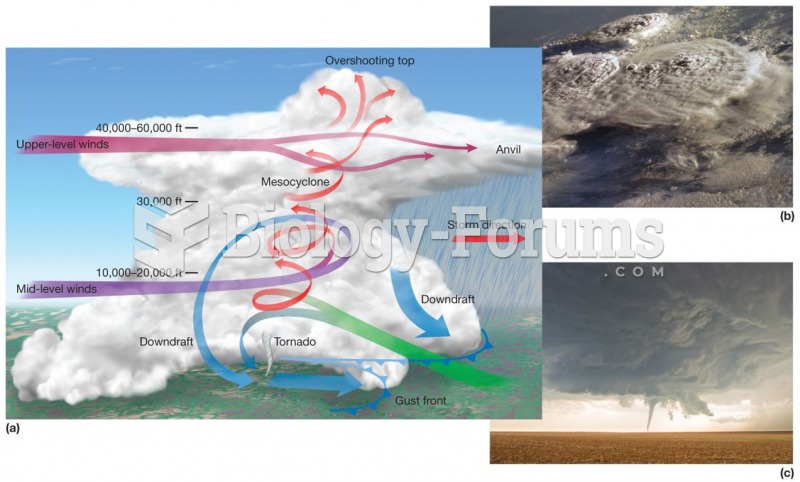

ANSWER: Thunderstorms that contain a number of cells, each in a different stage of development, are called multicell thunderstorms. Such storms tend to form in a region of moderate-to-strong vertical wind speed shear. In these storms wind speed increases rapidly with height, producing strong wind speed shear. This type of shearing causes the cell inside the storm to tilt in such a way that the updraft actually rides up and over the downdraft. The rising updraft is capable of generating new cells that go on to become mature thunderstorms. Precipitation inside the storm does not fall into the updraft (as it does in the ordinary cell thunderstorm), so the storms fuel supply is not cut off and the storm complex can survive for a long time. Long-lasting multicell storms can become intense and produce severe weather for brief periods. When convection is strong and the updraft intense, the rising air may actually intrude well into the stable stratosphere, producing an overshooting top. As the air spreads laterally into the anvil, sinking air in this region of the storm can produce beautiful mammatus clouds. At the surface, below the thunderstorms cold downdraft, the cold, dense air may cause the surface air pressure to risesometimes several millibars. The relatively small, shallow area of high pressure is called a mesohigh. The mesohigh increases the pressure gradient between the storm-cooled air and the warmer, unstable air that lies beyond the storm, a situation that raises the risk of high winds.

Answer to Question 2

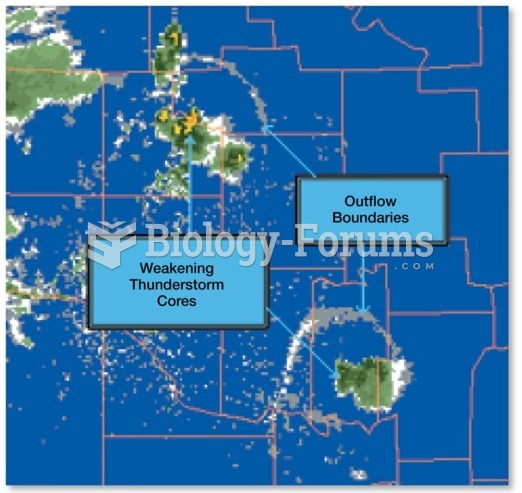

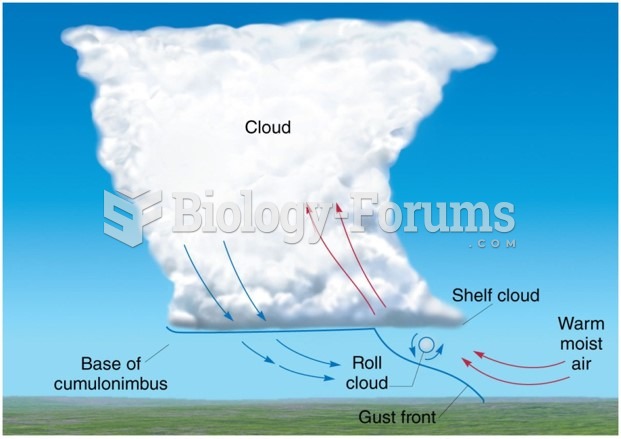

ANSWER: Ordinary thunderstorms, tend to form in a region where there is limited vertical wind shearthat is, where the wind speed and wind direction do not abruptly change with increasing height above the surface. Many ordinary thunderstorms appear to form as parcels of air are lifted from the surface by turbulent overturning in the presence of wind. Moreover, ordinary storms often form along shallow zones where surface winds converge. Such zones may be due to any number of things, such as topographic irregularities, sea-breeze fronts, or the cold outflow of air from inside a thunderstorm that reaches the ground and spreads horizontally. These converging wind boundaries are normally zones of contrasting air temperature and humidity and, hence, air density.

Ordinary thunderstorms go through a fairly predictable cycle of development from birth to maturity to decay. The first stage is known as the cumulus stage, or growth stage. As a parcel of warm, humid air rises, it cools and condenses into a single cumulus cloud or a cluster of clouds. The appearance of the downdraft marks the beginning of the mature stage. The downdraft and updraft within the mature thunderstorm now constitute the cell. In some storms, there are several cells, each of which may last for less than 30 minutes. After the storm enters the mature stage, it begins to dissipate in about 15 to 30 minutes. The dissipating stage occurs when the updrafts weaken as the gust front moves away from the storm and no longer enhances the updrafts. At this stage, downdrafts tend to dominate throughout much of the cloud. The reason an ordinary cell thunderstorm does not normally last very long is that the downdrafts inside the cloud tend to cut off the storms fuel supply by destroying the humid updrafts. Deprived of the rich supply of warm, humid air, cloud droplets no longer form. Light precipitation now falls from the cloud, accompanied by only weak downdrafts. As the storm dies, the lower-level cloud particles evaporate rapidly, sometimes leaving only the cirrus anvil as the reminder. A single ordinary cell thunderstorm may go through its three stages in one hour or less.