The transcontinental railroads were built and owned by private companies but financed by the public (with one exception, James J. Hill's Great Northern). The sparseness of population between the Mississippi Valley and California and Oregon (Washington State after 1889) made it impossible to attract private investors to railroads connecting the East and West. Construction was too expensive. Building a mile of track meant bedding 3,000 ties in gravel and attaching 400 rails to them by driving 12,000 spikes. Having built that mile in Utah or Nevada, a railroader had nothing to look forward to but hundreds more miles of scarcely inhabited desert mountains. With no customers along the way, there would be no profits; without profits, no investors. The federal government had political and military interests in binding the Pacific Coast to the rest of the Union, and, in its land, the The Pacific Railway Act of 1862 granted to two companies, the Union Pacific (UP) and the Central Pacific (CP), a right of way 200 feet wide between Omaha, Nebraska, and Sacramento, California. For each mile of track that the companies built, they were to receive, on either side of the tracts, 10 alternate sections (square miles) of the public domain. The result was a belt of land 40 miles wide, laid out like a checkerboard on which the UP and the CP owned half the squares. The railroads sold the land to provide the money for construction and created customers in the buyers. Or they used their vast real estate as collateral against which to borrow cash from banks. In addition, depending on the terrain, the government lent the two companies between 16,000 and 48,000 per mile of track at bargain interest rates. According to the passage, the railroad was mostly built through

a. densely populated cities.

b. swamps and marshlands.

c. mountains and deserts.

d. lush green forests.

Question 2

The transcontinental railroads were built and owned by private companies but financed by the public (with one exception, James J. Hill's Great Northern). The sparseness of population between the Mississippi Valley and California and Oregon (Washington State after 1889) made it impossible to attract private investors to railroads connecting the East and West. Construction was too expensive. Building a mile of track meant bedding 3,000 ties in gravel and attaching 400 rails to them by driving 12,000 spikes. Having built that mile in Utah or Nevada, a railroader had nothing to look forward to but hundreds more miles of scarcely inhabited desert mountains. With no customers along the way, there would be no profits; without profits, no investors. The federal government had political and military interests in binding the Pacific Coast to the rest of the Union, and, in its land, the The Pacific Railway Act of 1862 granted to two companies, the Union Pacific (UP) and the Central Pacific (CP), a right of way 200 feet wide between Omaha, Nebraska, and Sacramento, California. For each mile of track that the companies built, they were to receive, on either side of the tracts, 10 alternate sections (square miles) of the public domain. The result was a belt of land 40 miles wide, laid out like a checkerboard on which the UP and the CP owned half the squares. The railroads sold the land to provide the money for construction and created customers in the buyers. Or they used their vast real estate as collateral against which to borrow cash from banks. In addition, depending on the terrain, the government lent the two companies between 16,000 and 48,000 per mile of track at bargain interest rates. According to the passage, the railroads were able to obtain construction funds by

a. selling railroad stocks to private investors.

b. giving the construction workers a share of the profits.

c. applying for government grants.

d. selling land or getting low interest government loans.

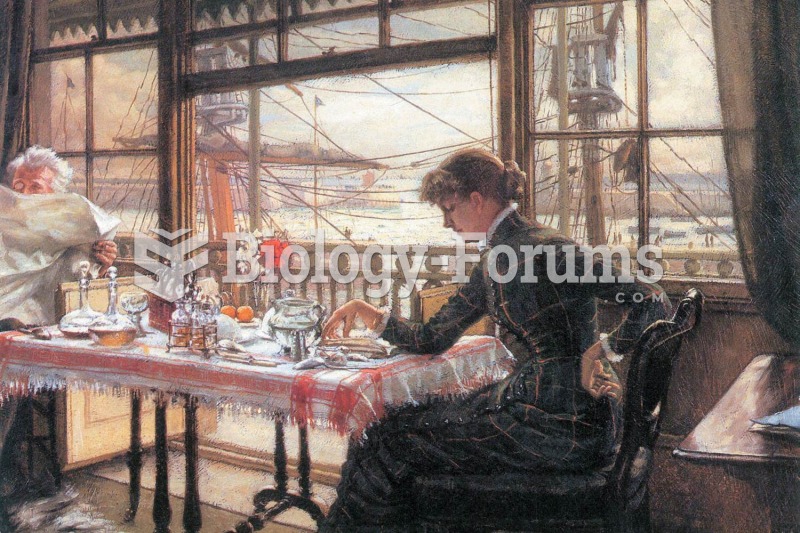

At breakfast, a middle-class husband sits absorbed in the newspaper and the public affairs of the da

At breakfast, a middle-class husband sits absorbed in the newspaper and the public affairs of the da

In this cartoon, Boss Tweed welcomes cholera—a skeletal figure of death carrying a handbag from “Asi

In this cartoon, Boss Tweed welcomes cholera—a skeletal figure of death carrying a handbag from “Asi