Answer to Question 1

b

Answer to Question 2

A QUESTION OF ETHICS

1. The secretary's regulation defining the term harm to include habitat modification that kills or injures wildlife can be viewed as consistent with the use of the term take to refer to the capture or killing of wildlife. Both definitions include kill as synonyms for their terms, and cap-turing wildlife involves injury, even if only to the animals' freedom. It can also be argued that the definitions are inconsistent. Take, as defined in the question, might be construed to require direct killing or capturing of wildlifethat is, applying force directly against an animal. Harm, as defined in the secretary's regulation, prohibits acts that indirectly kill or injure wildlifethat is, modifying animals' habitat with the effect of killing or injuring them. As the United States Supreme Court points out in its opinion, Congress did not define take so narrowly in the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 as to limit it to direct applications of force, and the Court in this case concluded that the secretary's definition of harm was con-sistent with the ESA.

2. Take, as defined in the ESA, includes harm. Harm, as defined in the regulation, in-cludes habitat modification where it actually kills or injures wildlife. In other words, the regulation is limited to habitat modification that causes actual, as opposed to hypothetical, death or injury to protected animals. Because habitat modification is part of the definition of harm, which is part of the definition of take, take can be construed as habitat modification.

One issue in this case, argued between Justice O'Connor in her concurring opinion and Justice Scalia in his dissent, was whether the ESA is limited to actions that actually kill or injure individual animals (existing generations) or whether it applies to populations, which Scalia interpreted to cover potential additions (future generations). In suggesting that the regulation could be extended to cover nonexistent animals, Scalia pointed out that the regulation includes a reference to breeding. Scalia argued against such an extension by claiming that impairment of breeding does not injure' living creatures.

O'Connor disagreed. She stated that to make it impossible for an animal to reproduce is to impair its most essential physical functions and to render that animal biologically obso-lete. In other words, impairing an animal's ability to breed is, in and of itself, an injury. O'Connor also explained that interfering with breeding injures living animals. Breeding, feed-ing, and sheltering are what animals do. If significant habitat modification, by interfering with these essential behaviors, actually kills or injures an animal , it causes harm' within the meaning of the regulation.

O'Connor explained, despite Scalia's suggestion regarding nonexistent animals, that the regulation does not apply to speculative harm: That a protected animal could have eaten the leaves of a fallen tree or could, perhaps, have fruitfully multiplied in its branches is not sufficient. In O'Connor's opinion, the harm' regulation applies where significant habitat modification, by impairing essential behaviors, proximately (foreseeably) causes actual death or injury to identifiable animals that are protected under the Endangered Species Act. In her opinion, merely preventing the regeneration of forest land not currently inhabited by actual birds is not covered.

3. The majority pointed out in its opinion that the broad purpose of the ESA supports the Secretary's decision to extend protection against activities that cause the precise harms Congress enacted the statute to avoid. The ESA is the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species ever enacted by any nation. Earlier statutes enacted in 1966 and 1969 did not include a prohibition against the taking of endangered species except on federal land. The ESA, however, applies to all land in the United States and to the Nation's territorial seas. The plain intent of Congress in enacting this statute was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost. This is reflected not only in the stated policies of the ESA, but in literally every section of the statute.

Responses as to whether private parties should bear the burden of these policies depend on scientific, economic, and other extra-legal principles and individual conclusions based on beliefs about government and the nature of people. What is the effect of the loss of individual animals or even whole species? What importance should be attached to this effect? What is the effect of imposing a burden on private parties to limit their use of resources to protect animals? What importance should be attached to this effect? Is it a proper role of government to be involved? Could people be trusted to protect against adverse effects without the government's involvement?

4. Answers to this question, like responses to the previous question, can depend on fundamental beliefs about the importance of the environment, people's use of resources, and other extra-legal considerations. In applying some environmental statutes, the economic welfare of private parties is taken into account, and the government is required to pay (under the Constitution's takings clause). Under other statutes, economic exploitation of resources is limited, regardless of the effect on the private parties involved, in favor of other priorities.

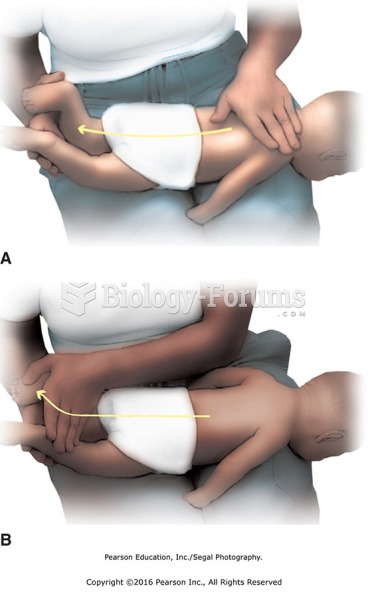

Slide along the bottom of the foot with the fist. Apply from the ball of the foot to the heel. Use ...

Slide along the bottom of the foot with the fist. Apply from the ball of the foot to the heel. Use ...

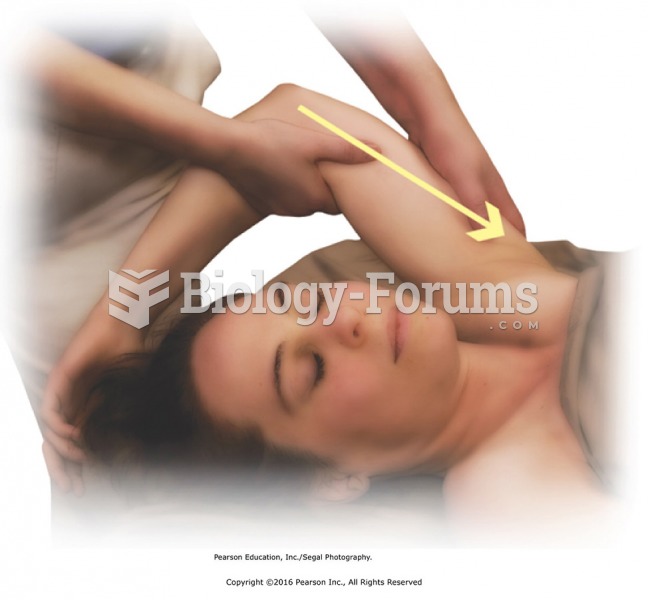

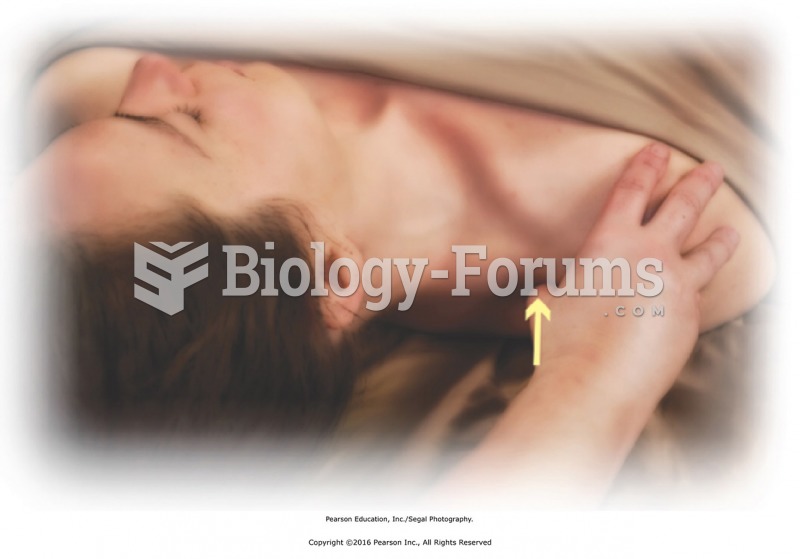

Apply direct pressure along upper trapezius, turning the head to access the area. Use your thumb to ...

Apply direct pressure along upper trapezius, turning the head to access the area. Use your thumb to ...