Answer to Question 1

TRUE

Answer to Question 2

A QUESTION OF ETHICS

1. The trial jury decided in favor of Biggins, and the appellate court concluded that there was sufficient evidence to support the jury's decision. In considering the appeal, the court held that there is no doubt that plaintiff here made out a prima facie case of age discrimination. He was within the protected age group. He was sixty- two years old at the time of his termination. He was performing his work at a level that met his employer's legitimate expectations. And he was replaced by someone younger than himself with roughly similar qualifications. Once a prima facie case is established, the burden shifts to the employer to articulate a legitimate nondiscriminatory reason for a discharge. As the court explained, the articulation of such a reason nullifies the inference raised by the prima facie case. Plaintiff must then clear the second hurdle by showing that the employer's articulated reasons were only a pretext for age discrimination. The key question is whether the employer fired plaintiff because of his age. In this case, Hazen articulated legitimate nondiscriminatory reasons for Biggins's discharge. The court outlined the most significant evidence on Biggins's claim: the confidentiality agreement that Hazen had asked Biggins to sign and the ensuing negotiations, which resulted in Hazen's telling Biggins to forego any additional compensation and to sign the agreement or he would be fired; Biggins's subsequent discharge a few weeks before his pension rights would have vested; Hazen's hiring a younger man to fill Biggins's former position on different confidentiality and non-compete terms; Hazen's suggesting to Biggins that he become a consultant, which would have cost Biggins all employee benefits; and Hazen's testifying that he knew age discrimination was illegal.

2. In the Biggins case, the court noted that by the mid-1980s, the coating that Biggins had developed while in Hazen's employ was being widely used by Hazen Paper. In 1983, Biggins became aware of the increase in Hazen's sales and of the fact that the commissions of one of Hazen's sales representatives had increased to over 200,000. Biggins felt that these sales commission were being made on something that I had developed' and sought an increase in pay. Hazen increased Biggins's salary by ten percent. But Biggins was dissatisfied and in 1984 again sought an increase in his salary, which by then was 44,000. At the trial, Biggins testified that he asked for 100,000, which the company refused to grant, but that the company president indicated that he would be willing to give me a piece of the company in stock. The president denied that he made that promise.

From ethical and economic points of view, however, giving an employee stock in the company could present the best solution to a dispute similar to the one that Hazen confronted with Biggins. Without raising the employee's salarywhich an employer might want to avoid in an effort to keep controllable company costs downgiving the employee stock could resolve the dispute with the employee, while rewarding him or her in a way that would tie his or her for-tunes to the company. Profit-sharing plans have also proven successful, as have bonuses tied to profit goals and stock purchase plans partially subsidized by employers. Alternatives include litigation and negative implications, such as arose in the Biggins case.

3. Most persons would agree that terminating an employee solely because of his or her age is unfair. Nevertheless, an employer may find it tempting, when economic times are difficult and the company is searching for ways to trim its payroll, to engage in what may appear to be age discrimination. Older, highly paid employees, particularly those who will be retiring in a few years, are often vulnerable to layoffs, because company managers want to keep younger, lower-paid workers, who are expected to do more work for less money. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission receives up to 17,000 age discrimination complaints each year, even though it prosecutes comparatively few of these cases itself. Most would-be plaintiffs must choose between litigating their own claims and doing nothing at all.

Whether a firing is discriminatory or a legal business decision is not always clear. Companies will generally defend a decision to discharge a worker on the ground that the worker could no longer perform his or her duties or that the worker's skills were no longer needed. The employee must prove that the discharge was motivated by age bias. Proof that qualified, older employees are generally discharged before younger employees or that coworkers continually made unflattering age-related comments about the discharged worker may be sufficient. From an ethical point of view, the employer may believe that the discharge of older workers helps to keep the company more cost-efficient, which may please other company constituenciesshare holders, customers, and younger employees, for example.

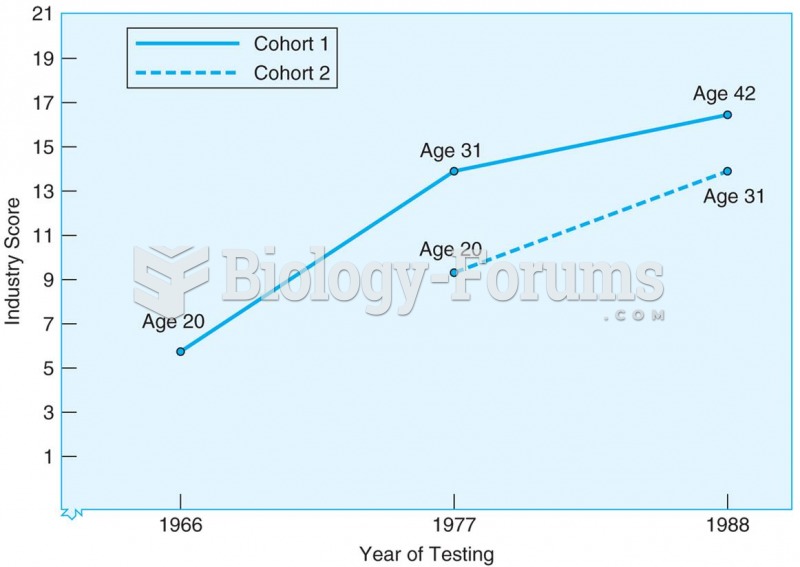

Results from sequential study of two cohorts tested at three ages and at three different points in t

Results from sequential study of two cohorts tested at three ages and at three different points in t

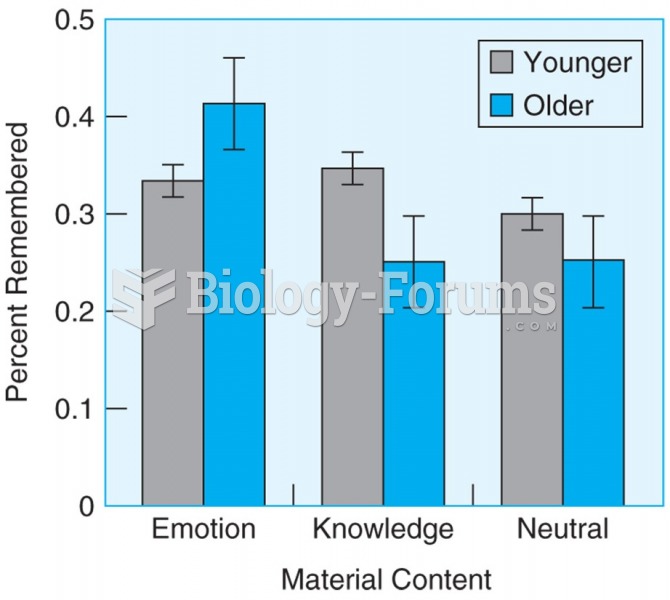

Older participants remember more information than younger participants when material has emotional ...

Older participants remember more information than younger participants when material has emotional ...

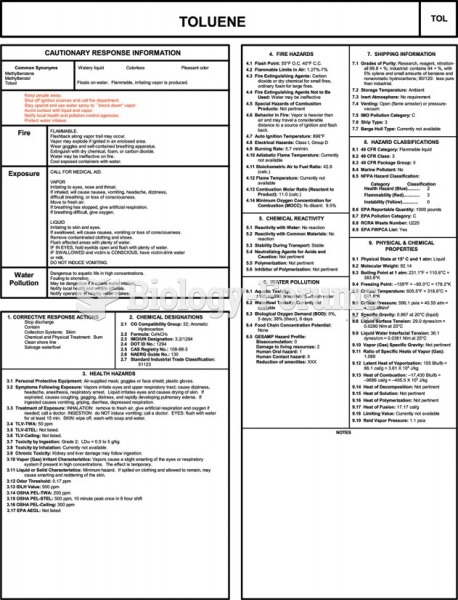

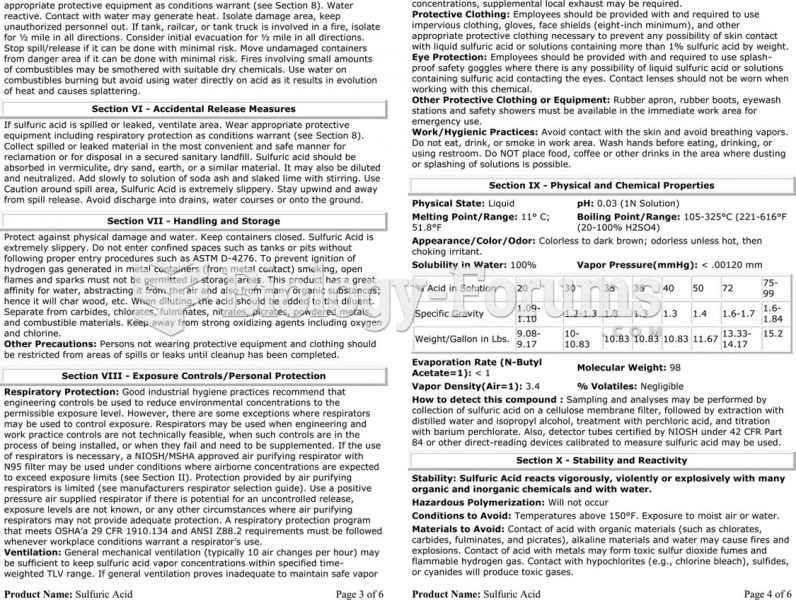

The material safety data sheet (MSDS) for sulfuric acid showing the detailed technical information ...

The material safety data sheet (MSDS) for sulfuric acid showing the detailed technical information ...