This topic contains a solution. Click here to go to the answer

|

|

|

Did you know?

Alzheimer's disease affects only about 10% of people older than 65 years of age. Most forms of decreased mental function and dementia are caused by disuse (letting the mind get lazy).

Did you know?

Patients who have been on total parenteral nutrition for more than a few days may need to have foods gradually reintroduced to give the digestive tract time to start working again.

Did you know?

Blood is approximately twice as thick as water because of the cells and other components found in it.

Did you know?

Approximately one in four people diagnosed with diabetes will develop foot problems. Of these, about one-third will require lower extremity amputation.

Did you know?

Thyroid conditions may make getting pregnant impossible.

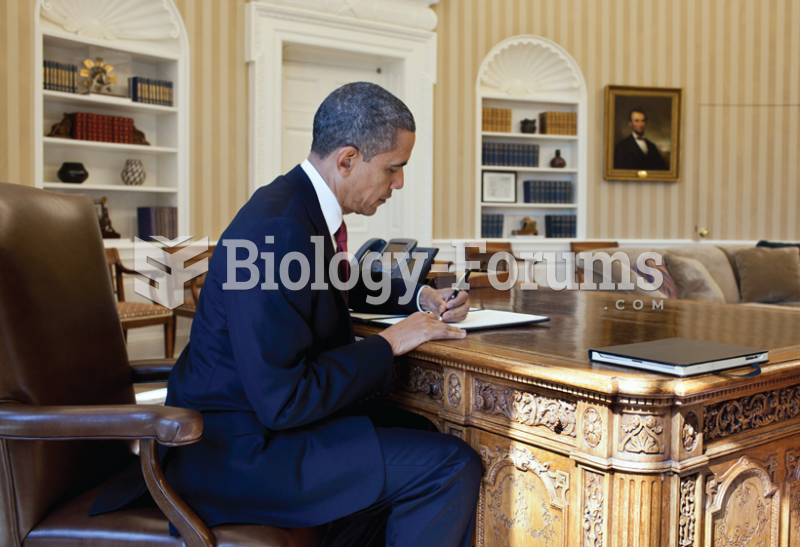

Blocked at every turn by congressional Republicans who hated him, President Obama turned to techniqu

Blocked at every turn by congressional Republicans who hated him, President Obama turned to techniqu

William Masters and Virginia Johnson are among the most influential researchers in the history of th

William Masters and Virginia Johnson are among the most influential researchers in the history of th

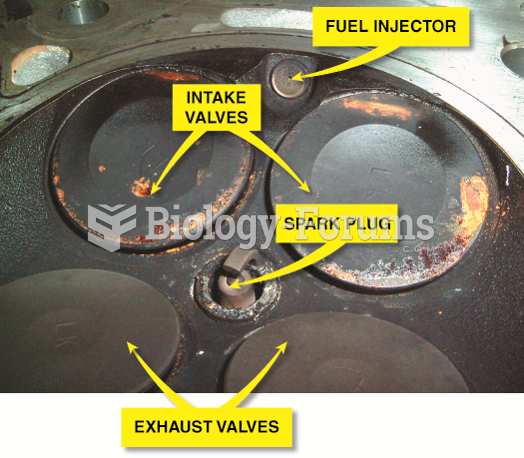

There may become a driveability issue because the gasoline direct-injection injector is exposed to ...

There may become a driveability issue because the gasoline direct-injection injector is exposed to ...