Answer to Question 1

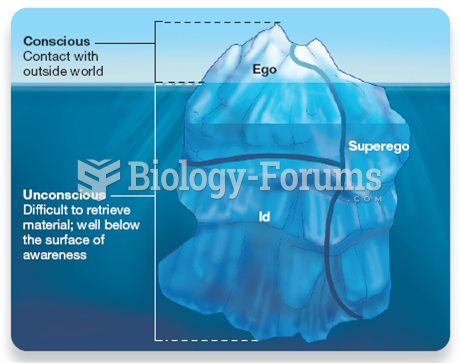

Answer: Anna Freud introduced a distinction between suppression, which is an ego activity in which an anxiety-provoking thought or memory is consciously kept under control, and repression, which is an unconscious process. Both Sigmund and Anna Freud believed that it was possible for the mind to repress a thought, memory, or feeling so deeply into the unconscious that it was forgotten. Contemporary research, however, does not support this model. Research in cognitive psychology suggests that attempting to put a thought out of our mind consciously or unconsciously only makes that thought occur more frequently. In addition, people generally do not forget a traumatic event; rather they work to alter their emotional response to an event that is too often remembered. Other evidence suggests that memories can be kept out of consciousness for periods of time, but that may be due to a decision to not talk about the event with family, friends, or researchers. Not talking about something is not the same as not remembering it. I would recommend that repression be removed from the list of defense mechanisms in favor of more contemporary concepts such as cognitive avoidance, retrieval inhibition, or memory bias.

Answer to Question 2

Answer: One of the most successful and applicable lines of psychological research is that of attachment theory. It was started by John Bowlby after WWII and continued experimentally by Mary Ainsworth and others, and it continues to be an active research area today. At the heart of attachment theory is the concept that human beings have evolved a set of behavior patterns for children and adults that have the survival advantage of keeping infants and caregivers in close contact. Infants are designed by evolution to expect a caregiver that will protect them and with the experience of close contact they come to trust their mother, feel relaxed in their presence and anxious in their absence and build a set of internal working models based on their early experiences of caregiving. Infants, who have the experience of a mother or caregiver who spends time with them and meets their basic needs for food, shelter, and contact, come to develop a secure attachment with their caregiver. Infants are genetically programmed to feel relaxed in the presence of their caregiver, but anxious and fearful in their absence.

A hospital situation that forces the separation of an infant or child from its caregiver therefore produces anxiety in the infant and the caregiver. Today, many hospitals have taken the research findings into consideration and either drastically reduce the rate of hospitalization of young children, as in the case of St. Judes, or make arrangements for families to spend a good deal of time, even sleeping overnight, with hospitalized children in order to maintain and foster secure attachment.