Answer to Question 1

Romantic artists sought to praise the hero, they captured certain principal themes that glorified creative individualism, patriotism, and nationalism. Antoine-Jean Gros, the student of first painter, Jacques-Louis David, painted works of Napoleon's military campaigns that became powerful vehicles of political propaganda. For example, in his Napoleon Visiting the Plague Victims at Jaffa, Gros converted a minor historical eventNapoleon's tour of his plague-ridden troops in Jaffa (in Palestine)into an exotic allegorical drama that cast Napoleon in the guise of Christ as healer. Indeed throughout most of Western history, the heroic image in art was bound up with Classical lore and Christian legend, but now artists were using this context to portray contemporary events. The artist Francisco Goya helped to advance this phenomenon. The Third of May, 1808: The Execution of the Defenders of Madrid was Goya's nationalistic response to the events ensuing from an uprising of Spanish citizens against the French army of occupation. In true Romantic style, he used emphatic contrasts of light and dark and the theatrical attention to graphic details to heighten the intensity of the contemporary political event.

Thodore Gricault worked to portray the heroic ideal as well, but chose to elevate ordinary men to the position of heroic combatants, as they struggle against insurmountable odds. His work The Raft of the Medusa brought together the reality of a man-made disaster and the more abstract theme of the Romantic sublime: the terror experienced by ordinary human beings in the face of nature's overpowering might.

While Goya and Gricault democratized the image of the hero, Gricault's pupil and follower Eugne Delacroix raised that image to grand proportions. His paintings are filled with fierce vitality and vivid detail, he declared, I have no love for reasonable painting. In his work, Liberty Leading the People, the women, a personification of liberty, assumes heroic status as she helps to lead the people against tyranny. Inspired by Delacroix's Liberty, France sent as a gift of friendship to the young American nation a monumental copper and cast-iron statue of a similarly idealized female symbol of liberty; The Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World) is the sister of Delacroix's painted heroine; it has become a classic image of freedom for oppressed people everywhere.

In his sculpture, Franois Rude embodied the dynamic heroism of the Napoleonic Era. In his richly textured work, The Departure of the Volunteers of 1792, Rude captured the revolutionary spirit and emotional fervor of this battalion's marching song, La Marseillaise, which the French later adopted as their national anthem.

Answer to Question 2

As with Romantic literature, artists and musicians reacted to the formality and intellectual discipline of Neoclassicism by embracing emotion and spontaneity. In place of the cool rationality and order of a Neoclassical composition, the Romantics introduced a studied irregularity and disorder.

The Romantic hero also appeared in countless paintings and sculptures. Romantic art glorified the creative individualism, patriotism, and nationalism embodied by this hero. Paintings strove to portray passion, desire, and emotional turbulence. Seeking to heighten intensity, artists often left their brushstrokes visible, as if to underline the immediacy of the creative act. They might deliberately blur details and exaggerate the sensuous aspects of texture and tone.

In music too, Romantic composers shared with the artists of their time the development of a more personal and unconstrained style. They tended to modify the rules of classical composition in order to increase expressive effect. They abandoned the clarity and precision of the classical composition, expanding and loosening form and introducing unexpected shifts of meter and tempo. Just as Romantic painters made free use of color to heighten the emotional impact of a subject, so composers gave tone color a status equal to melody, harmony, and rhythm. During the nineteenth century, the symphony orchestra reached heroic proportions, while smaller, more intimate musical forms became vehicles for the expression of longing, nostalgia, and love. Further, the virtuoso became a physical embodiment of the herodazzling in ability, egotistical, and praised to mythical proportions.

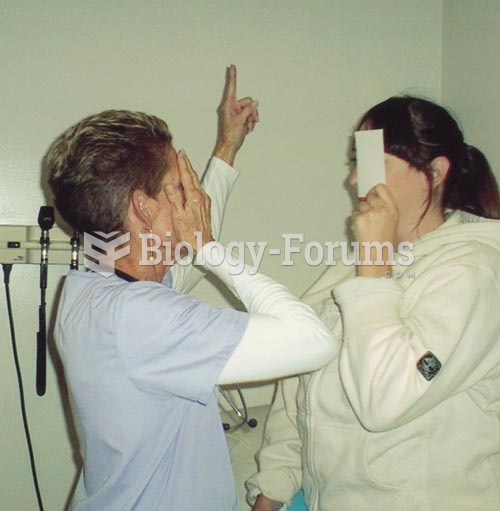

Testing Visual Fields by Confrontation: The nurse and patient should be approximately at an eye to e

Testing Visual Fields by Confrontation: The nurse and patient should be approximately at an eye to e

Vision with macular degeneration is experienced with an inability to focus in the center of the visu

Vision with macular degeneration is experienced with an inability to focus in the center of the visu