Answer to Question 1

Devotional realism followed the general trend in medieval arts to depict ordinary details of life, in an effort to make the ordinary more dramatic. For example, in Claus Sluter's Well of Moses, facial features of the prophets are individualized so as to render each one with a distinctive personality. In the illuminated manuscripts of the Book of Hours, scenes from sacred history are filled with realistic and homely details drawn from everyday life. Even miraculous events are made more believable as they are presented in lifelike settings and given new dramatic fervor. The brothers Limbourg produced a series of Books of Hours, illustrated with an attention to natural details: dovecote and beehives covered with new- fallen snow, sheep that huddle together in a thatched pen, smoke curling from a chimney, and even the genitalia of two of the laborers who warm themselves by the fire.

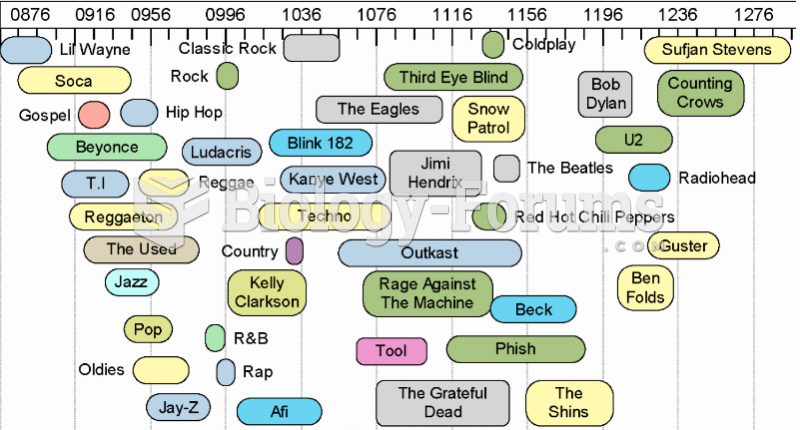

The new music of the time, ars nova, paralleled the richly detailed Realism apparent in fourteenth-century literature and the visual arts. The music featured a distinctive rhythmic complexity, achieved in part by isorhythm: the close repetition of identical rhythmic patterns in different portions of a composition. Isorhythm, an expression of the growing interest in the manipulation of pitches and rhythms, gave unprecedented unity to musical compositions. The composer Guillaume de Machaut wrote music that paid attention to expressive detail and his efforts at coherence of design is clear evidence that composers had begun to rank musical effect as equal to liturgical function. He also introduced new warmth and lyricism, as well as vivid poetic imageryfeatures that parallel the humanizing currents in fourteenth-century art and literature.

Answer to Question 2

During the late Middle Ages, warfare and poor economic conditions had been taking a toll on European people. In 1347, the bubonic plague, or Black Death, added to the misery, destroying 50 percent of its population in less than a century. Originating in Asia, the plague was carried into Europe by flea-bearing black rats infesting the commercial vessels that brought goods to Mediterranean ports. Within two years of its arrival it ravaged much of the Western world. In its early stages, it was transmitted by the bite of either the infected flea or the host rat; in its more severe stages, it was passed on by those infected with the disease. The plague hit hardest in the towns, where the concentration of population and the lack of sanitation made the infestation all the more difficult to contain. Four waves of bubonic plague spread throughout Europe between 1347 and 1375, attacking some European cities several times and nearly wiping out their entire populations.

For survivors of the plague, the aftermath was confusing as they tried to make sense of the horror in religious terms. Some viewed it as the manifestation of God's displeasure with the growing worldliness of contemporary society, while others saw it as a divine warning to all Christians, but especially to the clergy, whose profligacy and moral laxity were ubiquitous. Still others, in a spirit of doubt and inquiry, questioned the very existence of a god who could work such evils on humankind. The questioning of religions and church authority threatened tradition and shook the confidence of medieval Christians. Inevitably, the old medieval regard for death as a welcome release from earthly existence began to give way to a gnawing sense of anxiety and a new self-consciousness. Economically, the population decrease caused a shortage of labor, which in turn created a greater demand for workers. The bargaining power of those who survived the plague was thus improved. In many parts of Europe, workers pressed to raise their status and income and urban growth increased as jobs were readily available.

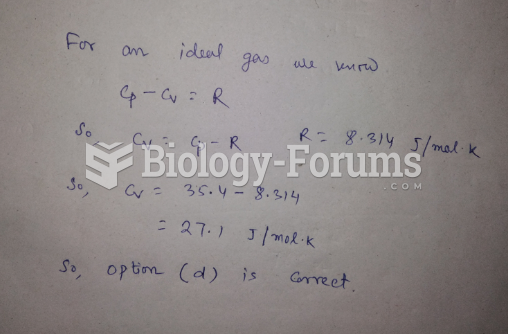

Answer to Question 3

C