|

|

|

In 1835 it was discovered that a disease of silkworms known as muscardine could be transferred from one silkworm to another, and was caused by a fungus.

People who have myopia, or nearsightedness, are not able to see objects at a distance but only up close. It occurs when the cornea is either curved too steeply, the eye is too long, or both. This condition is progressive and worsens with time. More than 100 million people in the United States are nearsighted, but only 20% of those are born with the condition. Diet, eye exercise, drug therapy, and corrective lenses can all help manage nearsightedness.

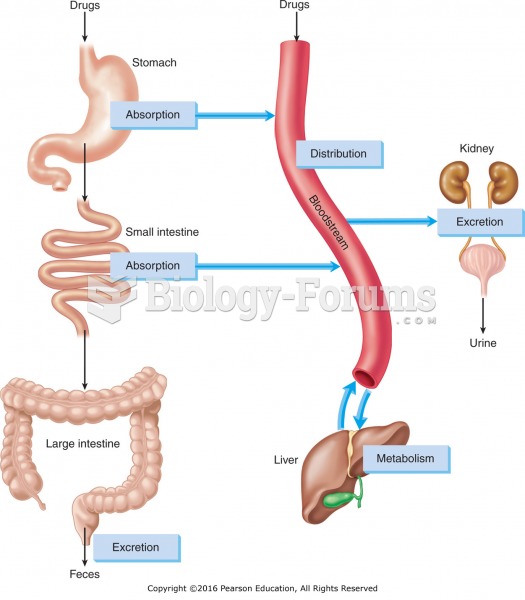

Though methadone is often used to treat dependency on other opioids, the drug itself can be abused. Crushing or snorting methadone can achieve the opiate "rush" desired by addicts. Improper use such as these can lead to a dangerous dependency on methadone. This drug now accounts for nearly one-third of opioid-related deaths.

Blood is approximately twice as thick as water because of the cells and other components found in it.

HIV testing reach is still limited. An estimated 40% of people with HIV (more than 14 million) remain undiagnosed and do not know their infection status.