Answer to Question 1

Serving healthful lunches is only half the battle; students need to eat them too. Short lunch periods and long waiting lines prevent some students from eating a school lunch and leave others with too little time to finish their meals. Nutrition efforts at schools are also undermined when students can buy what the USDA labels competitive or nonreimbursable foodsmeals from fast-food restaurants or a la carte foods such as pizza or snack foods and carbonated beverages from snack bars, school stores, and vending machines. When students have access to competitive foods, participation in the school lunch program decreases, nutrient intake from lunch declines, and more food is discarded.

Answer to Question 2

Children who are malnourished are vulnerable to lead poisoning. They absorb more lead if their stomachs are empty; if they have low intakes of calcium, zinc, vitamin C, or vitamin D; and, of greatest concern because it is so common, if they have an iron deficiency. Iron deficiency weakens the body's defenses against lead absorption, and lead poisoning can cause iron deficiency. Common to both iron deficiency and lead poisoning are a low socioeconomic background and a lack of immunizations against infectious diseases. Another common factor is picaa craving for nonfood items. Many children with lead poisoning eat dirt or chips of old paint, two common sources of lead.

The anemia brought on by lead poisoning may be mistaken for a simple iron deficiency and therefore may be incorrectly treated. Like iron deficiency, mild lead toxicity has nonspecific symptoms, including diarrhea, irritability, and fatigue. Adding iron to the diet does not reverse the symptoms; exposure to lead must stop and treatment for lead poisoning must begin. With further exposure, the symptoms become more pronounced, and children develop learning disabilities and behavioral problems. Still more severe lead toxicity can cause irreversible nerve damage, paralysis, mental retardation, and death.

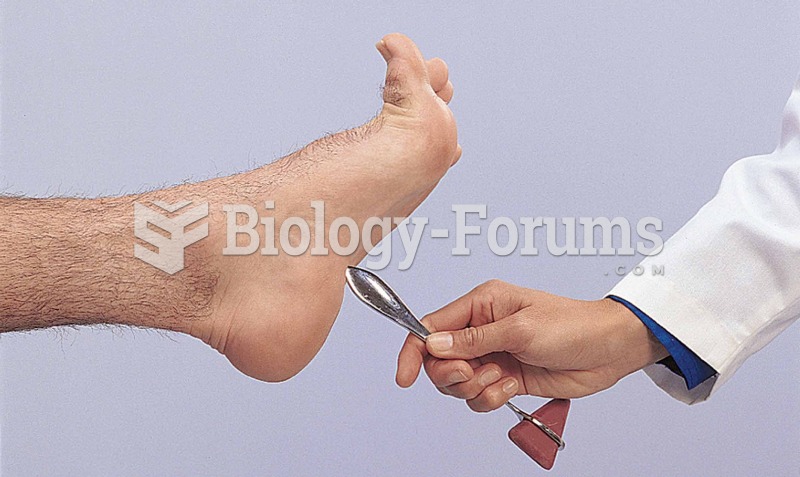

Approximately half a million children between the ages of 1 and 5 in the United States have blood lead concentrations above 5 micrograms per deciliter, the level at which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend public health actions be initiated. Lead toxicity in young children comes from their own behaviors and activitiesputting their hands in their mouths, playing in dirt and dust, and chewing on nonfood items. Unfortunately, the body readily absorbs lead during times of rapid growth and hoards it possessively thereafter. Lead is not easily excreted and accumulates mainly in the bones, but also in the brain, teeth, and kidneys. Tragically, a child's neuromuscular system is also maturing during these first few years of life. No wonder children with elevated lead levels experience impairment of balance, motor development, and the relaying of nerve messages to and from the brain. Deficits in intellectual development are only partially reversed when lead levels decline.