Answer to Question 1

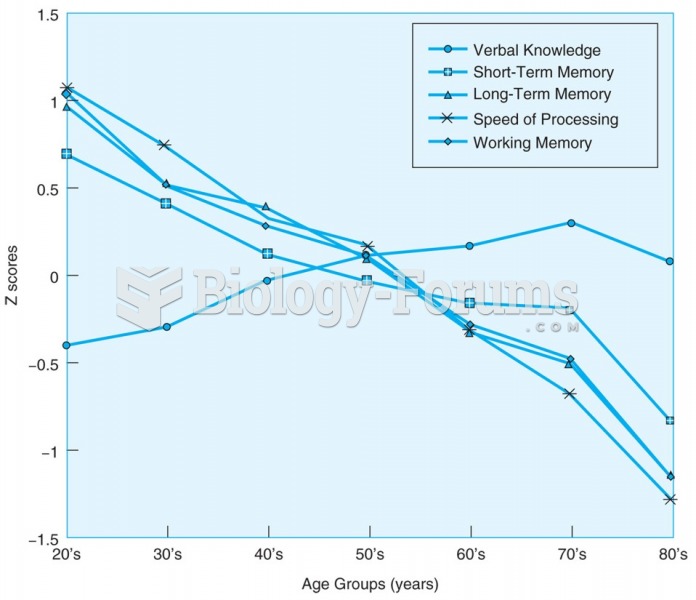

For a cross-sectional design, researchers take a cross section of a population across the different age groups and compare them on some characteristic. For example, if they were trying to understand the development of alcohol abuse and dependence, they could take groups of adolescents at 12, 15, and 17 years of age and assess their beliefs about alcohol use. In cross-sectional designs, the participants in each age group are called cohorts. The members of each cohort are the same age at the same time and thus have all been exposed to similar experiences. Members of one cohort differ from members of other cohorts in age and in their exposure to cultural and historical experiences. Differences among cohorts in their opinions may be related to their respective cognitive and emotional development at these different ages and to their dissimilar experiences. This cohort effect, the confounding of age and experience, is a limitation of the cross-sectional design.

One question not answered by cross-sectional designs is how problems develop in individuals. Rather than looking at different groups of people of differing ages, researchers may follow one group over time and assess change in its members directly. The advantages of longitudinal designs are that they do not suffer from cohort effect problems, and they allow researchers to assess individual change. Imagine conducting a major longitudinal study: not only must the researcher persevere over months and years, but so must the people who participate in the study. They must remain willing to continue in the project, and the researcher must hope they will not move away or, worse, die. Longitudinal research is costly and time-consuming. Finally, longitudinal designs can suffer from a phenomenon similar to the cohort effect on cross-sectional designs. The cross-generational effect involves trying to generalize the findings to groups whose experiences are different from those of the study participants.

Answer to Question 2

In psychological research, statistical significance typically means that the probability of obtaining the observed effect by chance is small. When one obtains statistical difference, is it an important difference? The difficulty is in the distinction between statistical significance (a mathematical calculation about the difference between groups) and clinical significance (whether or not the difference was meaningful for those affected). Concern for the clinical significance of results has led researchers to develop statistical methods that address not just that groups are different but also how large these differences are, or effect size. Calculating the actual statistical measures involves fairly sophisticated procedures that take into account how much each treated and untreated person in a research study improves or worsens. In other words, instead of just looking at the results of the group as a whole, individual differences are considered as well.