Answer to Question 1

The Fourth Amendment applies to searches and seizures. A search is an activity geared toward finding evidence to be used in a criminal prosecution. To define when a search takes place, two important factors need to be considered: (1) whether the presumed search is a product of government action and (2) whether the intrusion violates a person's reasonable expectation of privacy. The term seizure has a dual meaning in criminal procedure. First, property can be seized. Often, the result of a search is a seizure of property to be used as evidence.

Answer to Question 2

To define when a search takes place, two important factors need to be considered: (1) whether the presumed search is a product of government action, and (2) whether the intrusion violates a person's reasonable expectation of privacy.

The Fourth Amendment is limited to conduct that is governmental in nature. Thus, when a private individual seizes evidence or otherwise conducts a search, the protections of the Fourth Amendment are not triggered.

In Burdeau v. McDowell, 256 U.S. 465 (1921), the Supreme Court first recognized that the Fourth Amendment does not apply to private individuals. In that case, some private individuals illegally entered McDowell's business office and seized records that contained incriminating evidence against him. The records were later turned over to the Attorney General of the United States, who planned to use them against McDowell in court. The Supreme Court ruled that the records were admissible, and stated that the Fourth Amendment's origin and history clearly show that it was intended as a restraint upon the activities of sovereign authority, and was not intended to be a limitation upon other than governmental agencies (Id. at 475).

Government action alone is not enough to implicate the Fourth Amendment. The law enforcement activity must also infringe on a person's reasonable expectation of privacy.

In Katz, federal agents placed a listening device outside a phone booth in which Katz was having a conversation. Katz made incriminating statements during the course of his conversation, and the FBI sought to use the statements against him at trial. The lower court ruled that the FBI's activities did not amount to a search because there was no physical entry into the phone booth. The Supreme Court reversed that decision, holding that the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places, and so its reach cannot turn upon the presence or absence of a physical intrusion into any given enclosure. Instead, the Fourth Amendment definition of a search turns on the concept of privacy. In the Court's words, The Government's activities in electronically listening to and recording words violated the privacy upon which Katz justifiably relied while using the telephone booth and thus constituted a search and seizure' within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

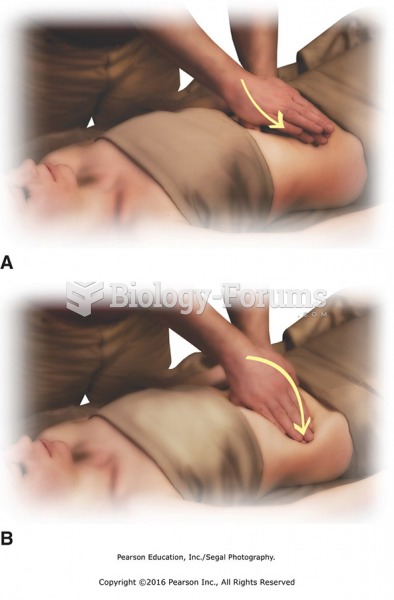

Apply petrissage to center of abdomen. Place hands palm over palm in center of the abdomen. Create ...

Apply petrissage to center of abdomen. Place hands palm over palm in center of the abdomen. Create ...

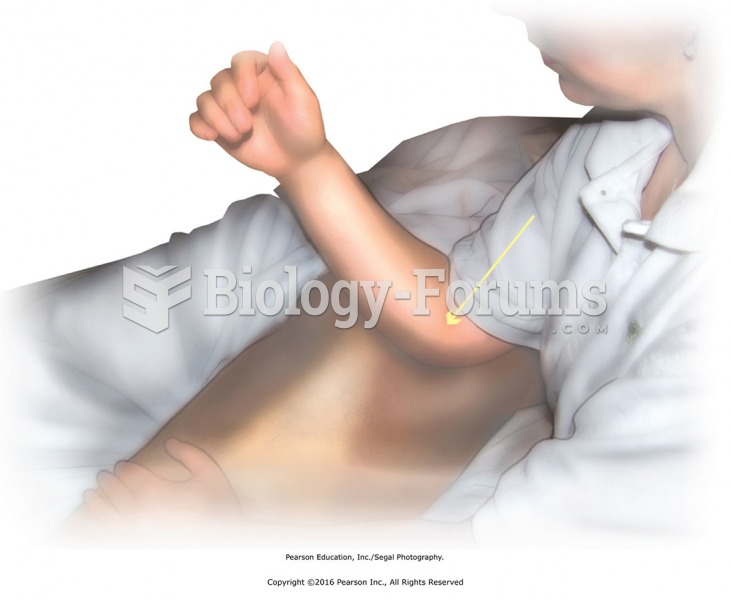

Direct pressure to deep rotator muscles using the elbow. Use the elbow tip to apply pressure moving ...

Direct pressure to deep rotator muscles using the elbow. Use the elbow tip to apply pressure moving ...