Answer to Question 1

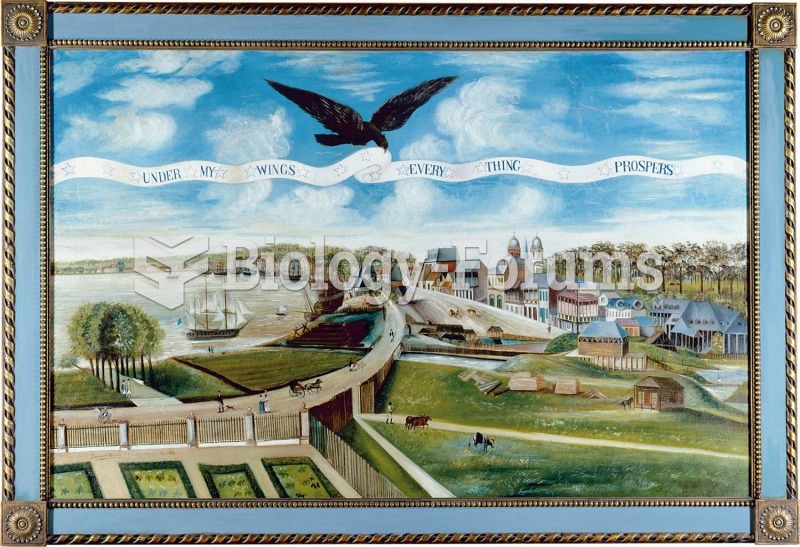

One of the main methods of totalitarian control is through propaganda, that is, manipulation of all the arts in order to further the controlling party's agendas. For example, in 1934, the First All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers officially approved the style of socialist realism in the arts. It condemned all manifestations of Modernism (from cubist painting to hot jazz) as bourgeois decadence. The congress called upon Soviet artists to create a true, historically concrete portrayal of reality in its revolutionary development. Artists were instructed to communicate simply and directly, to shun all forms of decadent (that is, modern) Western art, and to describe only the positive aspects of socialist society. Thus the arts served to reinforce in the public mind the ideological benefits of communism.

Music, especially, was controlled by totalitarian governments, as its inherent power to inspire was greatly feared. The Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev at first defended Soviet principles, proclaiming, The composer . . . is in duty bound to serve man, the people. He must be a citizen first and foremost, so that his art may consciously extol human life and lead man to a radiant future. The Soviets nevertheless denounced Prokofiev's music as too modern; and, along with his contemporary Dmitri Shostakovich, Prokofiev was relieved of his position at the Soviet music conservatories.

Film also provided a permanent historical record of the turbulent military and political events of the early twentieth century. It also became an effective medium of political propaganda. In Russia, Lenin envisioned film as an invaluable means of spreading the ideals of communism. Following the Russian Revolution, he nationalized the fledgling motion-picture industry. In the hands of the Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, film operated both as a vehicle for political persuasion and as a fine art. In America, film served as propaganda as well, working to inform, to boost morale, and to lobby for the Allied cause.

Answer to Question 2

The horrific conditions and consequences of the two world wars had a significant impact on the arts. Many writers, painters, and composers responded directly with visceral antiwar statements. Others, acknowledging the requirements of totalitarian regimes (those of Hitler in Germany, Stalin in Russia, and Mao in China), produced works that responded to the revolutionary ideologies of the state. Photography and filmmedia that appealed directly to the massesbecame important wartime vehicles, functioning both as propaganda and as documentary evidence of brutality and despair.

Poets and writers evoked themes of loss and hope for redemption and many, such as Wilfred Owen, criticized war as a senseless waste of human resources and a barbaric form of human behavior. After World War II, artists responded to the horrific violence with absurdity. Kurt Vonnegut and other gallows humor writers (a form of literary satire that mocks modern life by calling attention to situations that seem too ghastly or too absurd to be true) described the grotesque and the macabre in the passionless and nonchalant manner of a contemporary newspaper account.

Visual artists, such as Max Ernst, George Grosz, Fernand Lger, and Picasso, also incorporated the effects of war into their works. Most of these artists put forth impassioned protests, against the brutality and senselessness of modern warfare. Grosz, for example, mocked the German military and its corrupt and mindless bureaucracy in sketchy, brittle compositions filled with pungent caricatures. In Guernica, Picasso used a unique conjunction of powerful imagesa screaming woman, a dead baby, a severed arm, a victimized animalto create a universal icon for the inhuman atrocities of war, one that has made good his claim that art is a weapon against the enemy.

Twentieth-century composers were frequently moved to commemorate the horrors of war. The most monumental example of such music is the War Requiem (1963) by the British composer Benjamin Britten. Britten's imaginative union of sacred ritual and secular song calls for orchestra, chorus, boys' chorus, and three soloists. Poignant in spirit and dramatic in effect, this oratorio may be seen as the musical analogue of Picasso's Guernica. Similar in intent, the music of Krzysztof Penderecki seeks to capture the agony of war. His Threnody in Memory of the Victims of Hiroshima (1960) consists of violent torrents of dissonant, percussive sound, rapid shifts in density, timbre, rhythm, and dynamics, jarring and disquieting effects consistent with the subject matter of the piece.