Answer to Question 1

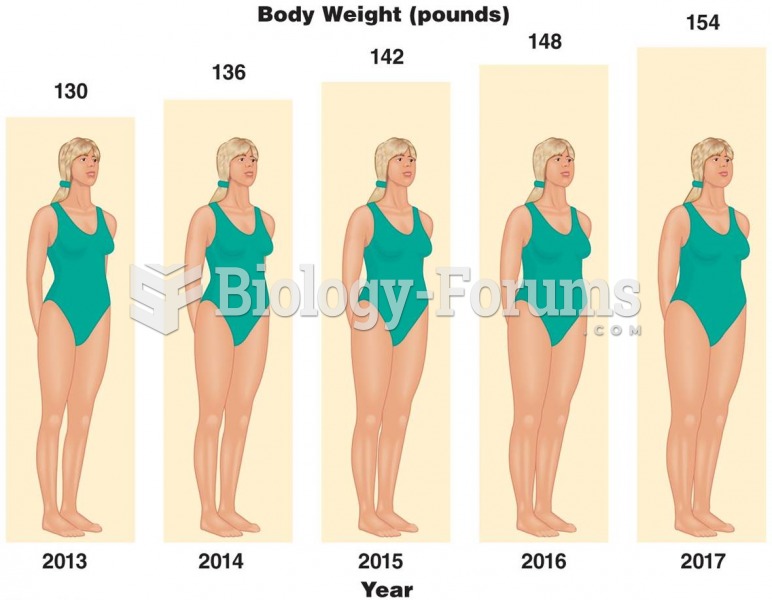

Answer: Today, 32 percent of U.S. children and adolescents are overweight, more than half of them extremely so: 17 percent are obese. Obese children are at risk for lifelong health problems. Symptoms that begin to appear in the early school yearshigh blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, respiratory abnormalities, insulin resistance, and inflammatory reactionsare powerful predictors of heart disease, circulatory difficulties, type 2 diabetes, gallbladder disease, sleep and digestive disorders, many forms of cancer, and premature death. Unfortunately, physical attractiveness is a powerful predictor of social acceptance. In Western societies, both children and adults stereotype obese youngsters as lazy, sloppy, ugly, stupid, self-doubting, and deceitful. In school, obese children and adolescents are often socially isolated. They report more emotional, social, and school difficulties, including peer teasing, rejection, and consequent low self-esteem. They also tend to achieve less well than their healthy-weight agemates. Persistent obesity from childhood into adolescence predicts serious psychological disorders, including severe anxiety and depression, defiance and aggression, and suicidal thoughts and behavior. These consequences combine with continuing discrimination to further impair physical health and to reduce life chances in close relationships and employment.

Answer to Question 2

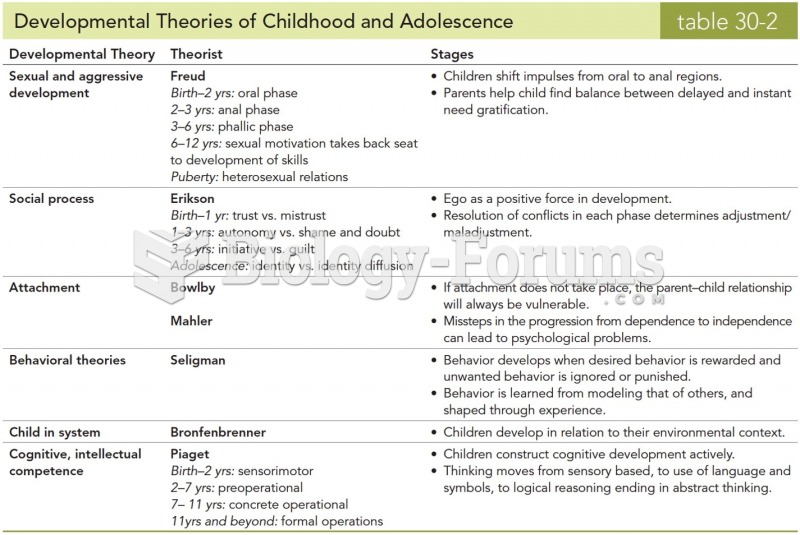

Answer: In village societies, conservation is often delayed. Among the Hausa of Nigeria, who live in small agricultural settlements and rarely send their children to school, even basic conservation tasksnumber, length, and liquidare not understood until age 11 or later. This suggests that participating in relevant everyday activities helps children master conservation and other Piagetian problems. Western children, for example, think of fairness in terms of equal distributiona value emphasized in their culture. They frequently divide materials, such as Halloween treats or lemonade, equally among their friends. Because they often see the same quantity arranged in different ways, they grasp conservation early. The experience of going to school promotes mastery of Piagetian tasks. When children of the same age are tested, those who have been in school longer do better on transitive inference problems. Opportunities to seriate objects, to learn about order relations, and to remember the parts of complex problems are probably responsible. Yet certain informal nonschool experiences can also foster operational thought. Around age 7 to 8, Zinacanteco Indian girls of southern Mexico, who learn to weave elaborately designed fabrics as an alternative to schooling, engage in mental transformations to figure out how a warp strung on a loom will turn out as woven clothreasoning expected at the concrete operational stage. North American children of the same age, who do much better than Zinacanteco children on Piagetian tasks, have great difficulty with these weaving problems. On the basis of such findings, some investigators have concluded that the forms of logic required by Piagetian tasks are heavily influenced by training, context, and cultural conditions.