Answer to Question 1

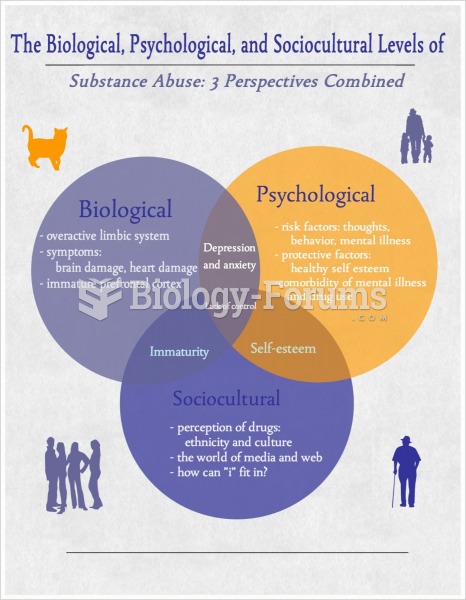

Inhalant abuse involves common household productsincluding whipped cream canisters, cooking sprays, deodorant and hair sprays, glues, nail polish remover, spray paints, gasoline, and lighter and cleaning fluidswhose vapors or aerosol gases are inhaled to get high. Also referred to as huffing or sniffing glue, these drugs are taken by volatilization and not following burning and heating, as is the case with tobacco, marijuana, or crack cocaine.

Even occasional or a single instance of inhalant abuse can be extremely dangerous. The effects include alcohol-like intoxication, euphoria, hallucinations, drowsiness, disinhibition, lightheadedness, headaches, dizziness, slurred speech, agitation, loss of sensation, belligerence, depressed reflexes, impaired judgment, and unconsciousness. As with other drug abuse, users can be injured by the harmful effects of the vapors and detrimental intoxication behavior.

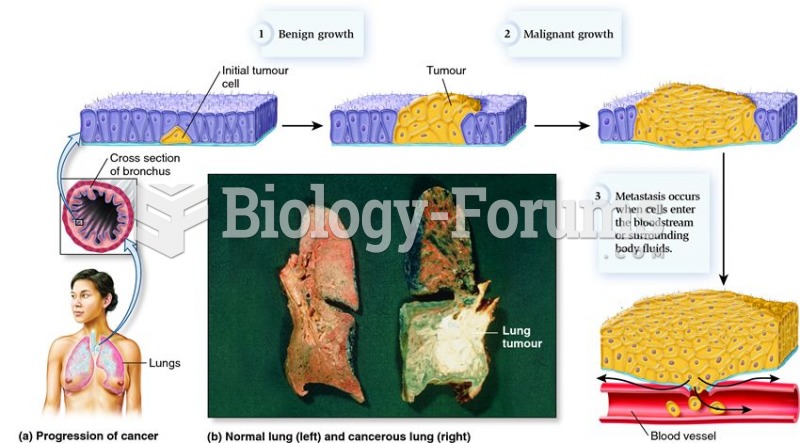

More serious consequences include suffocation due to lack of oxygen supply, pneumonia, vomit aspiration, organ damage (including to the brain, liver, and kidneys), abnormal heart rhythms, and sudden cardiac death. Inhalants are especially risky because they can be deadly at any time, even the very first time they are used. Inhalant abuse leads to a strong need to continue their use, and individuals abusing inhalants are more likely to initiate other drug use and have a higher lifetime prevalence of substance abuse.

Answer to Question 2

The trend of increased creativity in the preparation of synthetic psychoactive substances or spinoffs of known substances is fueled by widespread access to drug formulas via the Internet, and by the urgency of dealers to escape legislation that is constantly adapting in an effort to control known drugs. The United States Congress signed into law the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act (SDAPA) in July 2012, which identified 26 substances as Schedule I controlled substances, establishing drug codes for enforcement. Despite legislative efforts, however, small alterations in formulas by drug designers consistently outpace efforts to control or ban NPS. Each year the number of NPS far exceeds the number of substances that are put under regulatory control (the number of NPS globally more than doubled during the years 2009 through 2013).

Until they are placed under regulatory control, these substances are often marketed as legal alternatives to controlled drugs, said to be legal highs or herbal highs, to emphasize a seemingly safe and natural origin. Substances are also masked under the name of ordinary household products, such as bath salts, plant food, herbal incense, potpourri, or jewelry cleaner, to imply that they are both harmless and legal. In truth, some of these substances are so potent that that an amount as small as a grain of salt can produce adverse effects.

NPS are commonly referred to by both the general population and national associations as synthetic drugs or designer drugs, and are often labeled by dealers as research chemicals that are not for human consumption to avoid prosecution.