Answer to Question 1

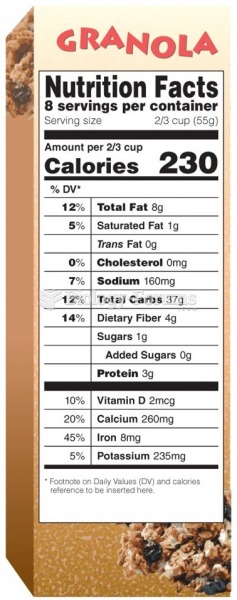

A nursing woman produces about 25 ounces of milk a day, with considerable variation from woman to woman and in the same woman from time to time, depending primarily on the infant's demand for milk. Producing this milk costs a woman almost 500 kcalories per day above her regular need during the first 6 months of lactation. To meet this energy need, the woman is advised to eat foods providing an extra 330 kcalories each day. The other 170 kcalories can be drawn from the fat stores she accumulated during pregnancy. During the second 6 months of lactation, an additional 400 kcalories each day are recommended. The food energy consumed by the nursing mother should carry with it abundant nutrients. Severe energy restriction hinders milk production and can compromise the mother's health.

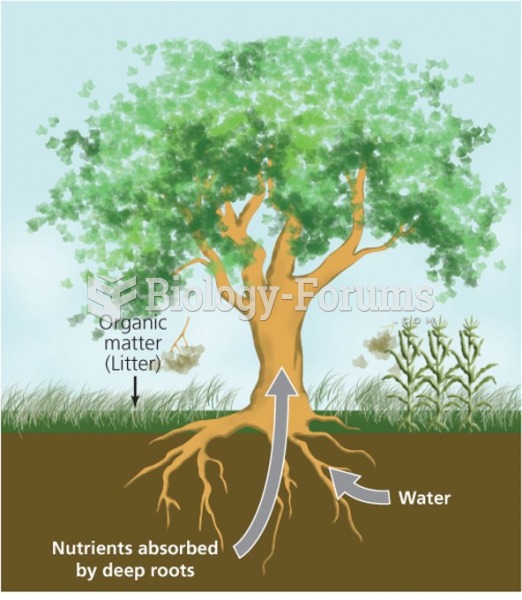

Women can produce milk with adequate protein, carbohydrate, fat, folate, and most minerals, even when their own supplies are limited. For these nutrients, milk quality is maintained at the expense of maternal stores. This is most evident in the case of calcium: dietary calcium has no effect on the calcium concentration of breast milk, but maternal bones lose some of their density during lactation if calcium intakes are inadequate. Such losses are generally made up quickly when lactation ends, and breastfeeding has no long-term harmful effects on women's bones. The nutrients in breast milk that are most likely to decline in response to prolonged inadequate intakes are the vitaminsespecially vitamins B6, B12, A, and D. Vitamin supplementation of undernourished women appears to help normalize the vitamin concentrations in their milk and may be beneficial.

Answer to Question 2

Constituents of cigarette smoke, such as nicotine, carbon monoxide, arsenic, and cyanide, are toxic to a fetus. Smoking during pregnancy can cause damage to fetal chromosomes, which could lead to developmental defects or diseases such as cancer. Smoking also restricts the blood supply to the growing fetus and so limits the delivery of oxygen and nutrients and the removal of wastes. It slows fetal growth, can reduce brain size, and may impair the intellectual and behavioral development of the child later in life. Smoking during pregnancy damages fetal blood vessels, an effect that is still apparent at the age of 5 years. It interferes with fetal lung development and increases the risks of respiratory infections and childhood asthma. A mother who smokes is more likely to have a complicated birth and a low-birthweight infant. The more a mother smokes, the smaller her infant will be. Of all preventable causes of low birthweight in the United States, smoking has the greatest impact. Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), the unexplained death that sometimes occurs in an otherwise healthy infant, has also been linked to the mother's cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Even in women who do not smoke, exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS, or secondhand smoke) during pregnancy increases the risk of low birthweight and the likelihood of SIDS.

Drinking alcohol during pregnancy threatens the fetus with irreversible brain damage, growth retardation, mental retardation, facial abnormalities, vision abnormalities, and many more health problemsa spectrum of symptoms known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, or FASD. Children at the most severe end of the spectrum (those with all of the symptoms) are defined as having fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which results in facial abnormalities. Less obvious is the internal harm: The fetal brain is extremely vulnerable to a glucose or oxygen deficit, and alcohol causes both by disrupting placental functioning. The lifelong mental retardation and other tragedies of FAS can be prevented by abstaining from drinking alcohol during pregnancy. Once the damage is done, however, the child remains impaired. An estimated 5 to 20 of every 10,000 children are victims of FAS, making it one of the leading known preventable causes of mental retardation in the world.

Caffeine crosses the placenta, and the fetus has only a limited ability to metabolize it. Research studies have not proved that caffeine (even in high doses) causes birth defects in human infants (as it does in animals), but limited evidence suggests that heavy useintake equaling more than 3 cups of coffee a dayincreases the risk of hypertension and miscarriage. Depending on the quantities consumed and the mother's metabolism, caffeine may also interfere with fetal growth. Lower doses of caffeine appear to be compatible with healthy pregnancies. All things considered, it may be most sensible to limit caffeine consumption to the equivalent of one or two cups of coffee a day.