Answer to Question 1

An estimated 2 to 10 percent of pregnancies in the United States are complicated by a condition known as gestational diabetes. Gestational diabetes usually develops during the second half of pregnancy, with subsequent return to normal after childbirth. Some women with gestational diabetes, however, develop diabetes (usually type 2) after pregnancy, especially if they are overweight. For this reason, health-care professionals strongly advise against excessive weight gain duringand afterpregnancy. Weight gains after pregnancy increase the risk of gestational diabetes in the next pregnancy.

The most common consequences of gestational diabetes are complications during labor and delivery and a high infant birthweight. Birth defects associated with gestational diabetes include heart damage, limb deformities, and neural tube defects. To ensure that the problems of gestational diabetes are dealt with promptly, physicians screen for risk factors and test high-risk women for glucose intolerance immediately and average-risk women between 24 and 28 weeks gestation.

Dietary recommendations should meet the needs of pregnancy and control maternal blood glucose. Diet and moderate exercise may control gestational diabetes, but if blood glucose fails to normalize, insulin or other drugs may be required. Importantly, treatment reduces preeclampsia, birth complications, large newborns, and infant deaths.

Answer to Question 2

A high-risk pregnancy is likely to produce an infant with low birthweight (LBW). Low-birthweight infants, defined as infants who weigh 5 pounds or less, are classified according to their gestational age. Preterm infants are born before they are fully developed; they are often underweight and have trouble breathing because their lungs are immature. Preterm infants may be small, but if their size and weight are appropriate for their gestational age, they can catch up in growth given adequate nutrition support. In contrast, small-for-gestational-age infants have suffered growth failure in the uterus and do not catch up as well. For the most part, survival improves with increased gestational age and birthweight.

Low-birthweight infants are more likely to experience complications during delivery than normal-weight babies. They also have a statistically greater chance of having physical and mental birth defects, becoming ill, and dying early in life. Of infants who die before their first birthdays, about two-thirds were low-birth-weight newborns. Very-low-birthweight infants (3 pounds or less) struggle not only for their immediate physical health and survival, but for their future cognitive development and abilities as well.

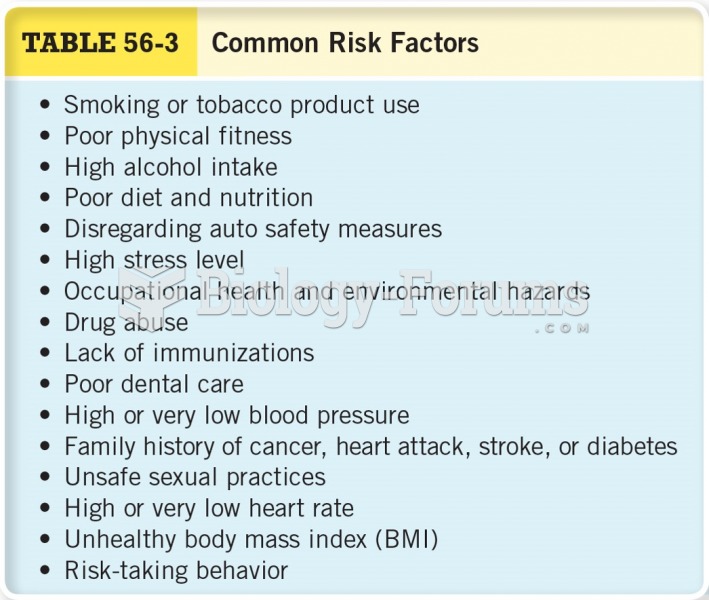

A strong association is seen between socioeconomic disadvantage and low birthweight. Low socioeconomic status impairs fetal development by causing stress and by limiting access to medical care and nutritious foods. Low socioeconomic status often accompanies teen pregnancies, smoking, and alcohol and drug abuseall predictors of low birthweight.