Answer to Question 1

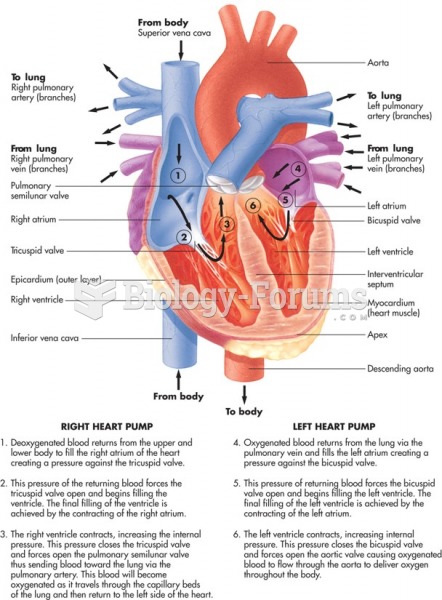

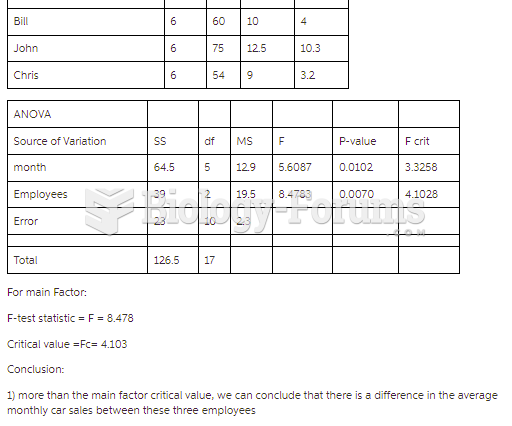

Heart failure can involve the left side, the right side, or both sides. However, it most often begins with the left ventricle. In left-sided HF, the left side of the heart experiences dysfunction and is unable to adequately maintain cardiac output. In right-sided HF, the right side of the heart cannot maintain cardiac output. Because the left and right sides of the heart have different functions, the resulting signs and symptoms caused by their failure are different. Though initial compensation by the body occurs, it cannot be maintained, and one-sided HF often expands to the entire heart, leading to decompensated HF.

Left-sided HF is typically the result of end-stage CAD or MI. When the left ventricle is damaged, it becomes weakened and cannot pump blood adequately to the systemic circulation. This can be further classified as systolic or diastolic. In systolic left-sided HF, the left ventricle has diminished contractility and cannot fully empty. In diastolic left-sided HF, the left ventricle experiences impaired relaxation and is unable to fill completely. Both of these situations lead to a decreased cardiac output and a resulting activation of the RAAS system in order to restore blood volume by increasing sodium and water reabsorption by the kidneys. The increase in fluid causes a backup of blood into the pulmonary circulation. The excess fluid in the pulmonary vein causes an increase in pressure in the pulmonary capillaries, and fluid is forced out of the vessels and into the lungs. This fluid makes it difficult to breathe, leading to dyspnea and tachypnea. Because the blood vessels lack the oncotic pressure to pull the fluid back out of the lungs, blood pressure remains low, and the system continues to stimulate the RAAS system to try to bring the body back to homeostasis. This leads to additional fluid accumulation and further pulmonary congestion.

Right-sided HF is most often the result of left-sided HF.3 When the right side of the heart begins to fail, it cannot maintain cardiac output to the pulmonary trunk. Again, the RAAS system is stimulated to retain sodium and water. This causes blood to back up into the systemic circulation. The high pressure in the periphery causes fluid to leak out into the third spaces near the feet and ankles as well as the liver and abdominal organs, resulting in pedal edema and ascites as well as splenomegaly and hepatomegaly. Additionally, venous pressure remains high, which results in the distention of the jugular vein in the neck and cerebral edema, which causes headache.

Both left- and right-sided HF lead to fatigue, dyspnea, and generalized weakness. Furthermore, the presence of edema in the abdominal region and dyspnea together cause a decrease in appetite/increase in satiety. This has many nutritional implications, including malnutrition and cardiac cachexia.

Answer to Question 2

Fiber and nutrient intakes (energy and protein), fluid and micronutrient balance, and pharmaconutrient interactions (protein and levodopa); both body weight gain and loss may occur during the course of the disease due to changes in both energy expenditure and food intake; dysphagia may be responsible for intake impairment and fluid balance; constipation, gastroparesis, and gastroesophageal reflux may occur with Parkinson's and affect quality of life and nutritional status

Mrs. McCormick has experienced a weight loss of 20 from UBW, as noted. She has trouble eating by mouth, based on the low PO intake and low fiber intake noted in her food recall (liquids mainly); lab values; and evidence of protein wasting (fat and muscle wasting, low Braden score). Constipation is indicated by dark/hard stools. GERD is indicated by her difficulty swallowing and feeling of choking; dehydration, by elements of her H&P such as poor skin turgor; and probable micronutrient deficiencies, by her angular stomatitis, cheilosis, koilonychia, and lab values suggesting anemia. Mrs. McCormick is likely experiencing dysphagia based on her difficulty swallowing and history of Parkinson's disease.